Gaston Of Chester

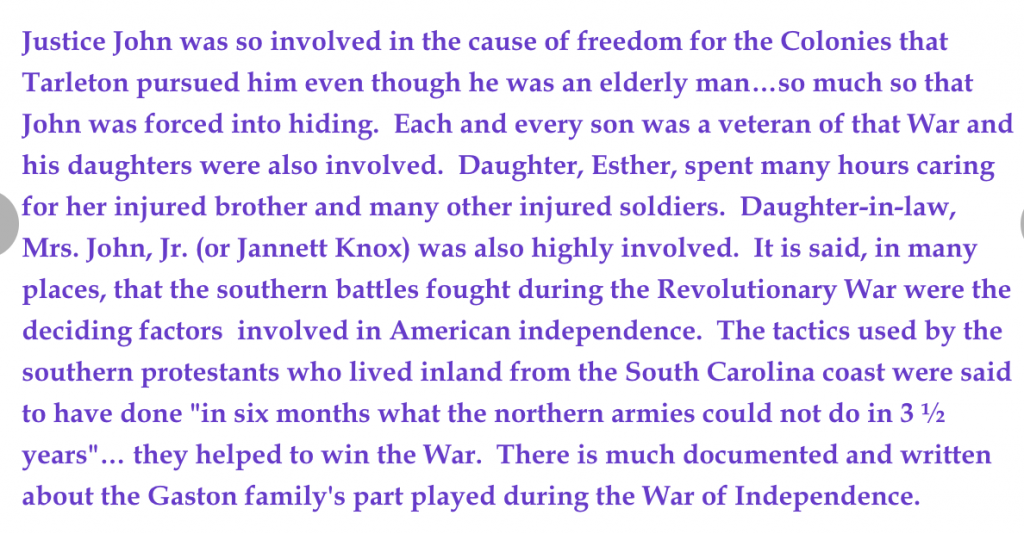

Based chiefly on the notes and records preserved by Judge Arthur Lee Gaston

Privately printed according to the will ofJudge Arthur Lee Gaston of Chester, South Carolina 1956

Liberty Or Death: The First Generation

- “A Reminiscence of the Revolution/’

by Joseph Gaston . 134

Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2018

Only the Prologue and first chapter are included as they apply to our family(Lundeen’s). The narrative is from reports from the posterity of Joseph Gaston youngest son to Justice John and Esther Gaston. The Lundeen line is through Justice John and Esther’s oldest son, Captain William Gaston who is also included in this story. Joseph who wrote down his families story is Captain William’s younger brother. For the full version of this book go to the following archived digital copy below:

PROLOGUE

(If the name is in bold then they are directly related to us)

Notes at the end are reference material for all dates, times, people, and related facts)

Even for South Carolina, a family which has maintained its prominence for two centuries in its original location is something of a rarity. The Gastons pioneered in the present Chester County twenty-five years before it received its name and have been there ever since. Of the Chester names notable before and during the Revolution, such as Lacey, McClure, Mills, Steel, Adair, and Gaston, only the Gastons have representatives of the male line yet living in the county. During the ante-bellum period (1800-1860), great planters, as the Davies, the DeGraffenrieds, the Randells, the Clouds and the McClures, occupied places of economic and social primacy, but they, too, have gone with the civilization which produced them.

The Gastons have never been the wealthiest family in the county. Their prominence has been in the professions. Amongst them have been judges, physicians, and Presbyterian clergymen second to none in the respect and affection of their fellow citizens. They have stood uniformly for education and morality. Their lives have been integrated with the development of the town and county from the early frontier days, through the plantation era, to the present business and industrial civilization. Since the American Revolution, they have been consistently conservative in politics, in religion, and in social attitudes. They have loved Chester and have not exploited their fellow citizens.

From the beginning, the Gastons have been family conscious. A considerable portion of Chester’s population shares this blood, though few at present bear the name. Most of those of Gaston descent are proud of their heritage and proud of the sacrifices their forebears made to maintain it.

The scope of this article does not entail an investigation of European origins. The pioneers brought with them few worldly goods. But they brought their family traditions. It is unimportant, perhaps, whether or not the American Gastons go back to the family of Gaston de Foix of sixteenth century France, But it is significant that he should have been claimed as a kinsman by Joseph Gaston of Cedar Shoals, an American backwoodsman, born before the Revolution and reared with limited educational and social opportunities. Joseph always spoke of Gaston de Foix with’pride and said ‘‘that after the lapse of centuries [his brothers and cousins in South Carolina] had sustained the name of Gaston in the battles of the Revolution.” It is somewhat surprising that the pioneer Gastons of Fishing Creek should have known of Gaston de Foix at all. But since the exploits of the precocious Count appear to have been a conscious example to the Revolutionary soldiers of his name in South Carolina, this history may appropriately begin with a notice of his career.

The family of Foix was of old French lineage and took its title of count from the district of Foix, later the department of Axiege in the south of France. Gaston de Foix was the grandson of Gaston IX and the last of this line of counts. He was born in 1489, the son of Jean de Foix and Marie de Orleans, sister of Louis XII. In the Italian wars waged by Louis, Gaston displayed the most brilliant and precocious genius and won the title of the Thunderbolt of Italy. The climax and conclusion of his career came when he was only twenty-three years of age.

In the great battle of Ravenna in 1512, the French and Spanish stood face to face on the sunny plains of Italy. One day there came a crisis in the fighting. Two battalions of Spanish infantry were about to break through the French lines. Gaston de Foix determined to lead a charge against them. His men pressed about him, begging and pleading with him not to throw his life away. But while they urged, he suddenly broke away, crying:

“Let him who loves me, follow me!” and spurred his horse toward the enemy’s lines. They looked but a moment. Then every knight of France, every hard old soldier, every peasant with his pike pressed after him. The Spanish were not used to giving way, but they gave way. The French were not used to breaking through, but they broke through. When the sun went down that day, Gaston de Foix lay dead on the field and lying near him were priest and peasant, nobleman and hired soldier. But the lions of Aragon had gone down in defeat and the lilies of France waved over the field. A youthful Gaston had established a family tradition.

Joseph Gaston was on more tenable ground when he told his children about their immediate ancestor Jean Gaston, the Huguenot. This Jean was banished from France by the Catholics and fled to Calvinist Scotland about the middle of the seventeenth century. His property was confiscated but his brothers and relatives who remained Catholics in France sent means to Scotland for his living. One anecdote concerning this founder of the Protestant branch of the family was brought by his descendants to South Carolina: Jean Gaston (Lundeen GGP) was a devout man and the worst words he was ever heard to say were on the occasion of his hurting his mouth with a fork, an implement just coming into table use. Jean Gaston exclaimed “Devil take the fork!” And his Calvinistic progeny remembered it for one hundred years.

The sons of Jean Gaston emigrated from Scotland to County Antrim, Ireland, probably during the 1660’s, a time of religious persecution in Scotland. Which of the sons was the ancestor of the South Carolina Gastons is not known but John Gaston appears on the hearth-money rate list for Ireland in 1669 as of Magheragall, County Antrim. It is certain that William Gaston (Lundeen GGP), grandson of the Huguenot Jean, lived at Clough Water, County Antrim (near Ballymena) Ireland, and was the father of the first of the name in Carolina. From the neighborhood of Ballymena, also, came the brothers John and Alexander Gaston, ancestors respectively of the Massachusetts and western states Gastons.”

Little is recorded of William Gaston of Clough Water (Lundeen GGP). He married a Miss Lemon (Lundeen GGP), reared a large family, and appears to have been a typically hard-working, hard-thinking member of that Scotch Presbyterian community. The lilting French originally spoken in the family had doubtless given way to the Gaelic in use by their neighbors. And the differences between the Huguenot and Presbyterian faiths, both Calvinistic, were easily forgotten. There were a number of Huguenot families who reached America by way of a generation or two in northern Ireland and identified their habits of thought and manner with the Ulster Scots. Among those who thus came to the Carolinas were the Gastons, Brevards, Pickens,’ Caldwells and Pettigrews.

The nine sons and daughters of William Gaston (Lundeen GGP) of CloughWater, their wives, their husbands, and their children, left Ireland for the new world for both religious and economic reasons. England’s efforts to control the linen and woolen industries of Ireland for her own profit and her determination to enforce support of the Anglican church, which the Calvinists opposed, drove thousands of sturdy peasants to the colonies. Many settled on the frontier from Pennsylvania to Georgia, conquered the Indians, conquered the wilderness, and eventually conquered the Redcoats sent to subject them again to British control. With the last victory, the ties with the ‘‘old countree” were forever severed, and a new era in history began.

CHILDREN OF

WILLIAM AND MARY (Olivet) LEMON GASTON —CLOUGH WATER, COUNTY ANTRIM, (Lundeen GGP)

IRELAND

- John married Esther Waugh (Lundeen GGP)

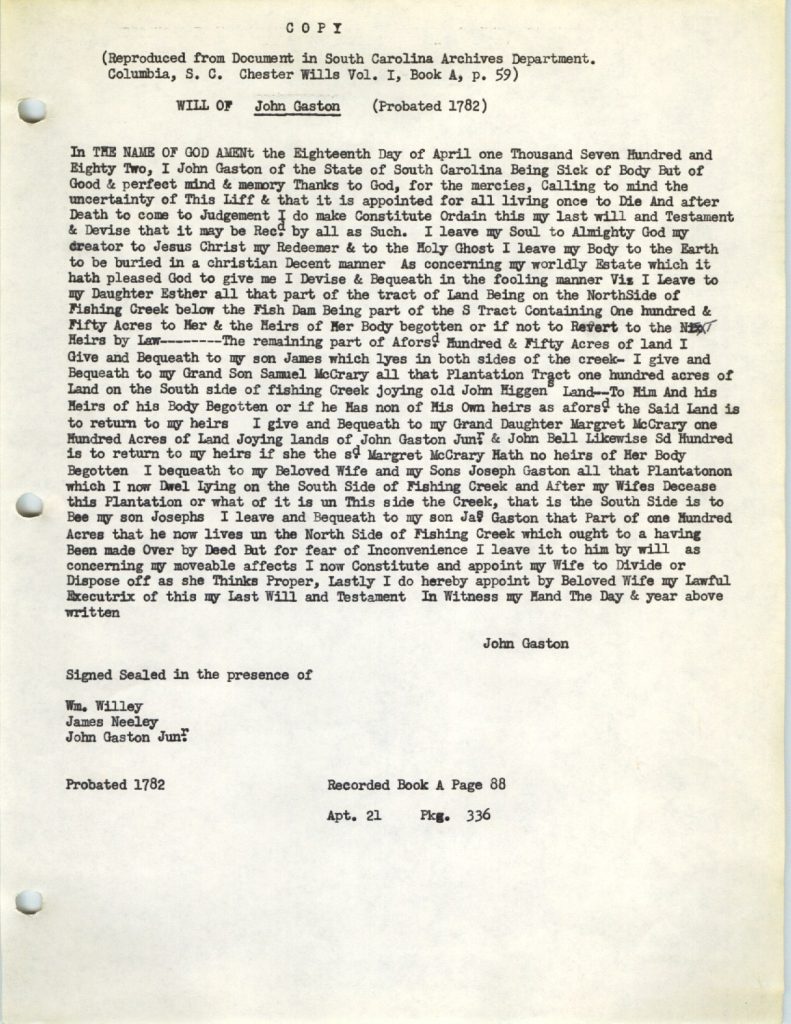

Justice of the Peace in Craven (later Chester) County, So. Carolina Died 1782. Will in Chester, So. Carolina

- Elizabeth married John Knox

Lived in Chester County, S. C.

- Hugh married Mary, daughter of Rev. James Thomson

Presbyterian minister and author in Ireland–Died in S. C., October 20, 1766.

- Mary married James McCluer ,(it’s how it’s spelled in his will)—Lived in Chester County, S. C.

His will in Charleston, S. C., 1771, hers in Chester, S. Carolina in 1802

- Robert married

Lived on Lynchs Creek, Lancaster County, S. C.

- Jinny married Charles Strong

Lived in Chester County, S. C.

- William married Jane Harbison

Drowned at Kell’s Ford, Chester County, S. C., about 1790

- Martha married Alexander Rosborough

Lived in Chester County, S. C.

- Dr. Alexander married Margaret Sharpe

Physician in New Bern, N. C. Killed by Tories, August 20, 1781.

For these families see Mrs. Elizabeth F. Ellet, The Women of the American Revolution, III (New York, 1852), and Charles Hanna, Ohio Valley Genealogies (New York, 1900).

THE GENERATIONS —The Author’s Lineage to Justice John Gaston

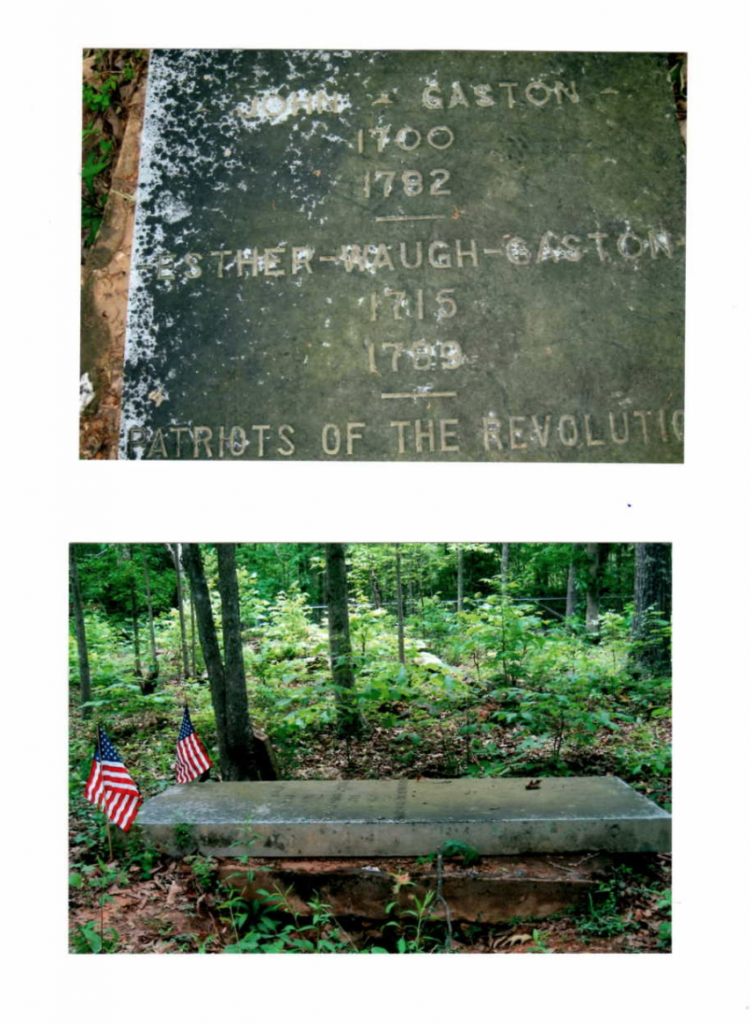

I Justice John Gaston — Esther Waugh (Lundeen GGP)

1710-1782 1715-1789

II Squire Joseph Gaston — Jane Brown

1763-1836 1768-1858

III Dr. John Brown Gaston — Mary Buford McFadden

1791-1864 1805-1886

IV Solicitor T. Chalmers Gaston — Adelaide Lee

1847-1885 1854-1895

V Judge Arthur Lee Gaston — Virginia Aiken

1876-1951 1881-1907

VI David Aiken Gaston — Reubie G. Holliday

1903- 1908-

VII Arthur Lee Gaston

1937-

Liberty Or Death

The First Generation of Gastons in America- And The Revolutionary War

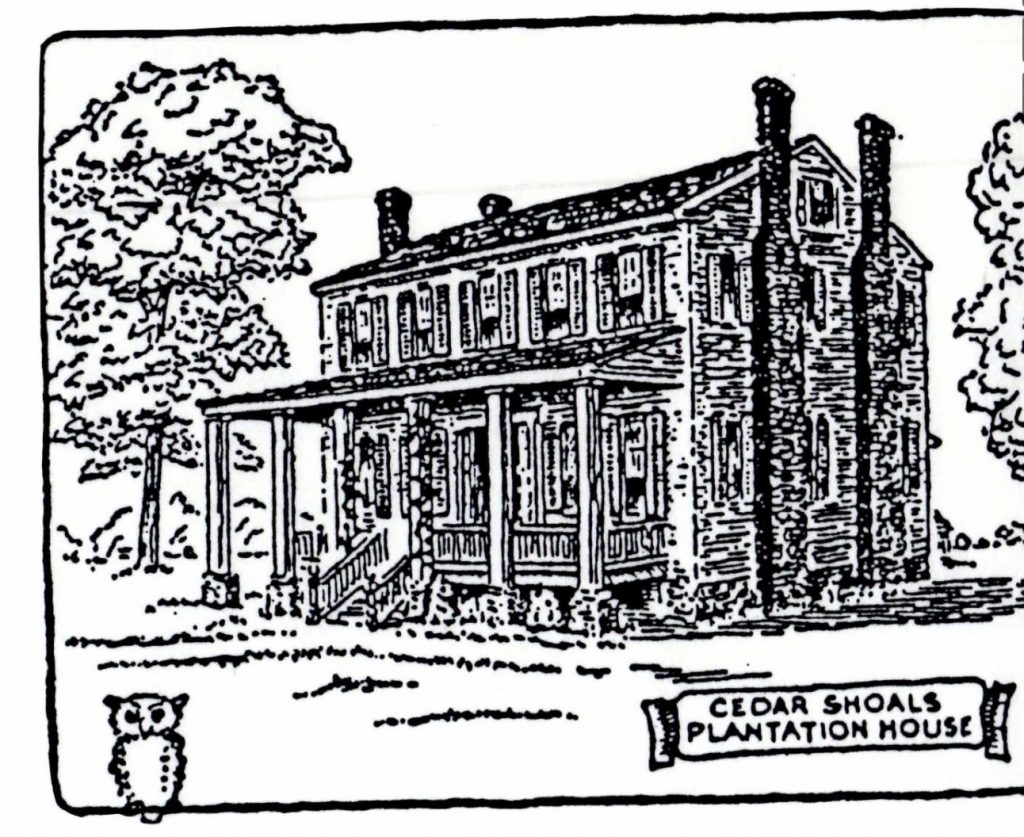

The First of the Gastons in South Carolina was John (Lundeen GGF), eldest son of William Gaston(Lundeen GGF), of Clough Water, County Antrim, Ireland. Prior to settling in South Carolina, he brought his family to Pennsylvania and accounts differ respecting several of his children as to whether they were born in Ireland or in the middle colonies. The two youngest, however, claimed to be native South Carolinians. This would date the emigration of the Gastons to South Carolina sometime between 1750 and 1760. They settled in the piedmont section of that colony, in the valley of the Catawba River, in the present Chester County, and there on the south side of Fishing Creek, six miles from its junction with the Catawba, John Gaston (Lundeen GGF) built his log house. John (Lundeen GGF) owned and probably named the land by the creek shallows known as Cedar Shoals, the designation for the Gaston plantations for four generations. The earliest recorded land grant to John Gaston (6th GGF) on the waters of Fishing Creek in Craven County is dated 1760, and in the same year his brother-in law James McCluer also obtained grants in that locality. Craven was one of the original four counties of South Carolina and included most of the interior of the colony.

The first Mrs. Gaston of what is now Chester County was Esther Waugh (Lundeen GGP) of northern Ireland. She and John Gaston were married in the *‘old country” and their eldest child was born there on August 29, 1739. Esther Gaston (Lundeen GGP) eventually bore her husband eleven more children who grew to maturity. She is notable, in addition to her prodigious maternity, as instructress for one of the up-country’s first schools, patronized chiefly by her own and her in-laws’ progeny. It was indeed no mean accomplishment for womankind of her time and place to be able to read and write at all, as is amply evident from the cross-marks in surviving colonial records.

In addition to farming, John Gaston(Lundeen GGP) supported his family by surveying, and much of the virgin forest inhabited by the Catawba Indians was first marked off for the white man’s use by his labors. History records that he was ‘’one of His Majesty’s surveyors and celebrated for the accuracy of his plats.”

The earliest distinction for the American family came on June 6, 1764, when Lieutenant Governor William Bull appointed John Gaston (Lundeen GGP) a justice of the peace for Craven County. The entry in the journal of the Governor’s Council reads:

“John Gaston having been recommended as a Majestrate for Craven County his name was inserted in the Commission of the Peace and it was reseal’d by His Honour.'”

Since the only courts outside Charles Town were those of the justices of the peace, the appointment carried considerable prestige and John was known as “Justice Gaston” for the rest of his life. Many first families of the up-country got a similar start in South Carolina and among the Craven County justices appointed along with Gaston were Cantey, Pickens, Wade and Pegues.

The duties of the justices in keeping the peace were many and varied. They included jurisdiction in cases involving not over about three pounds sterling, issuing warrants for the arrest and transportation of offenders to the provincial courts, hearing appeals of servants with grievances against their masters, giving certificates of ownership of horses, and enforcing the Sunday law. The prerogatives did not, however, include performing the marriage ceremony, as was permitted in North Carolina. In South Carolina, the ministers had a monopoly of this lucrative practice. The justices were paid by fees and were aided in law enforcement by constables and the local militia.

Justice Gaston (Lundeen GGP) was annually reappointed to office through out the colonial period (his section of Craven County being included in Camden District in 1769) and after the outbreak of the Revolution he was elected to the same office by the General Assembly of South Carolina. He became the most influential individual in his region of the Catawba valley and was largely responsible for its law-abiding reputation.

The Justice broadened his Cedar Shoals plantation by successive grants from the King, and while it was never a great estate in the low-country sense, it was large for the up-country, consisting of about one thousand acres. But slaves were few and luxuries fewer on the frontier. The family was of sufficient size to provide continuous assistance to the parents, Margaret, the oldest daughter, being twenty-three years old and already a mother when her youngest brother, Joseph, was born. The boys helped on the farm and with the livestock and occasionally made the wagon trips to Charles Town with their father. When they grew up, they were given land by Justice John (Lundeen GGP) or took out grants of their own, married, and settled nearby as independent farmers. The girls spun and wove and learned Presbyterianism and the practical arts from their mother. Clothes were made of flax and wool. Relics remembered by later generations included an old flax needle and spinning wheel in an outhouse and several pewter dishes belonging to Esther Gaston. The few books were chiefly of religious nature and included the Westminster shorter and longer catechisms. For intellectual and social stimulation, the family went to meeting to hear the long sermons of the Reverend William Richardson whose ministry at lower Fishing Creek church began in 1759.

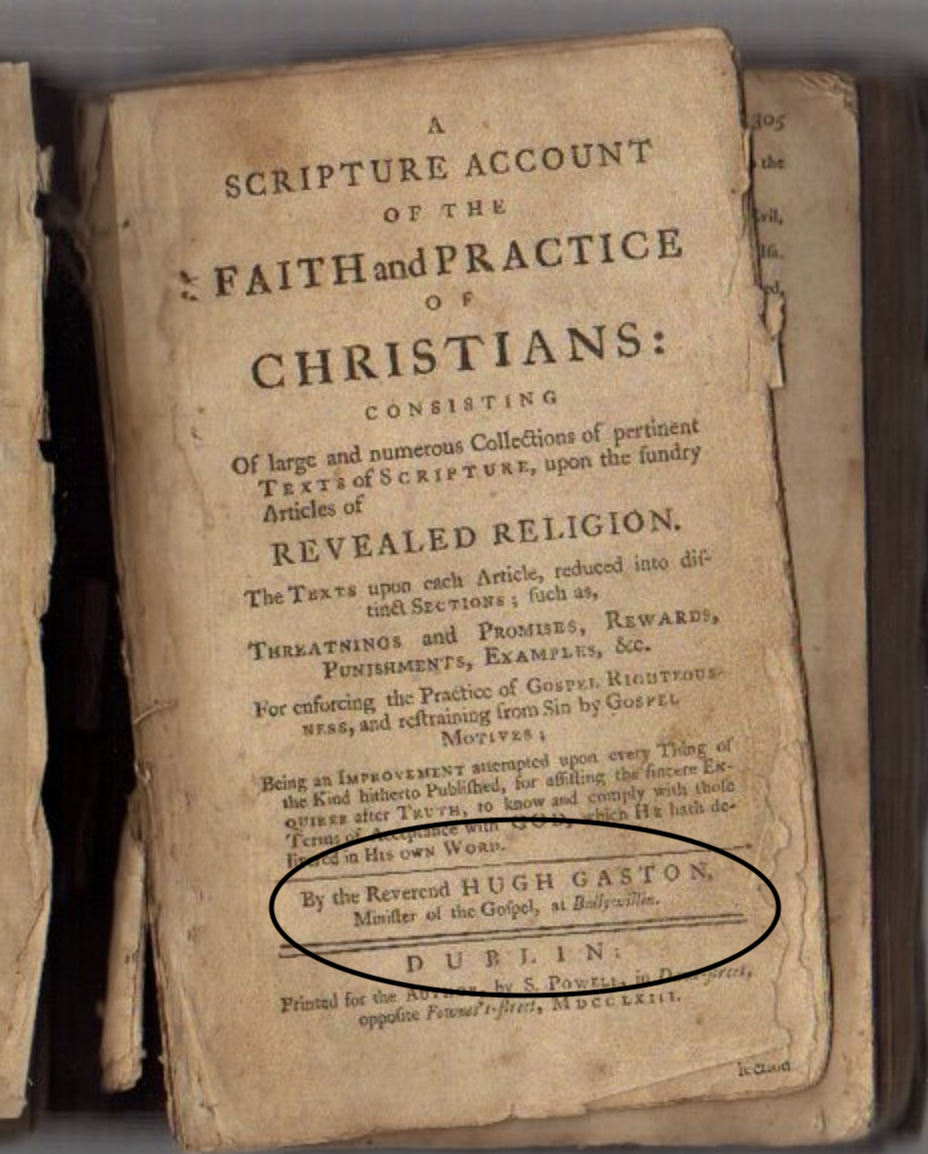

John Gaston (Lundeen GGP) and his sister Mary (Mrs. James McCluer) were probably the first of the connection in the Catawba valley. In 1776, the most distinguished of the brothers arrived in South Carolina. This was the Reverend Hugh Gaston of Root Presbytery, County Antrim, Ireland. In 1763, Hugh Gaston had published in Dublin A Scripture Account of the Faith and Practice of Christians and was on the way to becoming a household name for numerous Presbyterians in Ireland and America. The book was predestined to run through many editions on both sides of the Atlantic, but of this the author never knew. He had been ordained in Ballywillin in 1748, married Mary, daughter of the Reverend James Thomson, and fathered a large family. The story of his arrival in America and his untimely death is told in a letter by his brother John to Hugh’s wife in Ireland. It is the earliest personal letter now known from the present Chester County. Charles Town June 3, [8?], 1767

Dear Sister,

It is with a heavy heart I take my pen in hand to give you the news of your dear husband’s and my brother’s death.

He landed in Charles Town the twenty and first day of August last. My brother wrote from there to me for a horse to bring him to my house, and another to carry his clothes. The man who got the letter for me forgot to deliver it and carried it fifty miles past me — which caused my brother to stay in Charles Town till the fifteenth or sixteenth of September. When I got the letter I sent down a horse for my brother, and agreed with Capt. James Patton, one of my neighbors that was going to Charles Town to bring my brother’s clothes back in his waggon. I would have gone down to accompany my brother from town, but was obliged to go and survey land for some people whose Warrents were in my hand at the time. Not withstanding I got affairs so ordered that I got time to go about thirty miles to meet him. My brother-in-law, James McClure went with me — we came home by the Revd. William Richardson’s, our minister, and stayed there all night, and the Revd. Mr. Richardson gave my brother a list of twenty and two vacant congregations, and gave him directions how to go from one to another of them and told him there was a large field to labor in — and was much rejoiced that he had gotten another fellow-laborer in that part of God’s vineyard — and so were many vacant congregations glad to hear of his being come to this country. But all these joys and expectations were soon to be blasted. My brother came home with me from Mr. Richardson’s on Wednesday, the 24th of September, and stayed at my house till the Sabbath following, when my brother, my family and me rode to our meeting house together. My brother preached there that day which was his last sermon.

He complained a little on Saturday evening that he seemed to have caught a cold when he went out to the top of the hill before my door to see if he could get a view of the country and stayed out till the sun was set. He was troubled a little with cough and complained of a pain in his head. He went after Sermon with brother James McClure and sister Mary to their home. He had appointed to preach at a meeting house fourteen miles farther up Fishing Creek the following Friday. The next Sabbath, at Sermon, I heard he was so much indesposed he was unable to keep his appointment. My wife and I went to brother McClure’s to see brother Hugh. He did not complain much of anything but a great pain in his head. He said he wondered that his strength was gone with so little sickness. He felt he had a great drout, and when he lay in bed did not eat much.

When changing his shirt we saw his back full of red spots, like one that had measles. He washed and shaved himself and seemed indifferent well, only complained that his strength was so much gone.

He took physic which the doctor sent him. My wife and I went home that day which was Monday. I came again myself to see him on Thursday next — he was then so bad that he did not know me until midnight.

The next day we got him to rise up with our help, and I opened a vein in his foot, and gave him a little of the British oil inwardly and he seemed much better, and recovered his senses and his speech, and we were in hopes he was then in the way of recovery. About sunset he told me he had a mind to take some medicine the doctor had sent him. I advised him as he was then weak, and the night coming on, to let it alone until the next morning, which he consented to do. About dark he fell into a sound sleep which he had not done for three or four nights before. We thot that all danger of death was over. I went to bed having been up all the night before. About midnight they came in and wakened me, and told me he had gotten worse — they knew it by his breathing. He never wakened, but went off as if he had been in a sleep. He died about an hour and a half before day on the 20th of October last [1766]. He went off the easiest of any one I ever saw depart this life. He was buried on the 21st day of October at our meeting house on Fishing Creek. My eldest daughter, Margaret, died a little time after him, and left four children behind her. She was buried by my brother. My brother’s death was lamented by all in general, even by those who never saw or knew him, for it was thot that if he had lived to go home to Ireland he would have been the means of bringing more ministers with him to the Province, knowing what great need there is for ministers here, and what large salaries they get.

I received three letters from you, two from your brother James Thomson, and one from Cousin William. I also received a letter from a gentleman in Boston, addressed to my brother, which says he had sold five pounds Stirling worth of my brothers book, and he had the money ready for him whenever he pleased to send for it. The gentleman’s name I think was Moody.

Dear Sister, I understand by your writing and your brother James letter what circumstances you are in — in respect of your family affairs, my brother Hugh never told me how it was with him. If you and your family will come to this Country, brother-in-law James McClure and I would do what we could for you in helping to clear land and help to get you settled. There is about 20 pounds Stirling here for you and if you do not come I will send it to you by the first safe hand. I desire that you and your brother James and any of the family that can write, would please write me frequently, if you do not come to this Country, and let me know how all is with you, and my honored Father, and all friends.

I conclude with love to you, and all your family and all the rest of our friends with you. I remain your loving brother until death,

John Gaston (Lundeen GGP)

The Reverend Hugh Gaston brought with him his books, including a number of copies of his own which was a concordance of Bible quotations (later editions being entitled Gaston’s Collections) and his sermons. Had he lived, he would have conferred great credit on his family in South Carolina as a minister and author. Some of his grandchildren later emigrated to the northern states but none settled in South Carolina.

The youngest son of William Gaston of Clough Water, Ireland, and the youngest brother of Justice John (Lundeen GGP) and the Reverend Hugh, was Alexander. He became a physician and, according to tradition, studied for a time at the University of Edinburgh, the medical center of the British empire. He joined the Navy and sailed as ship’s surgeon. In the early 1760’s, he bought land in New Bern, N. C. On one or more occasions, he visited his brothers and sisters in upper South Carolina. He left at Cedar Shoals his manuscript notebook, 1766-1767, in which were the names of his patients, their ailments and his treatments. The Gastons preserved the notebook and on its blank pages transcribed family records, quotations, debts and credits. Dr. Alexander Gaston became the father of the most notable of all American Gastons, Judge William of the North Carolina Supreme Court. A pastel portrait of Dr. Alexander Gaston came down in the family of the Reverend Hugh in Ireland and was sent to America from Dublin in the twentieth century when that line became extinct.” It was Dr. Alexander who set the precedent for medicine as a family profession. At least half a dozen Gastons, and dozens of descendants of other names, have achieved conspicuous success in that calling.

Justice John’s brothers Robert and William followed him to South Carolina sometime before the Revolution. His sisters, Elizabeth (Mrs. John Knox), Mary (Mrs. James McCluer), Jinny (Mrs. Charles Strong), and Martha (Mrs. Alexander Rosborough) all lived in the Fishing Creek neighborhood and all appear in Mrs. Ellet’s Women of the Revolution as heroines of the War for Independence. Joseph Gaston wrote that when the Reverend Hugh Gaston came to South Carolina “he brought with him several copies of Gaston’s collections and gave one to my Father and each of his four sisters, Mrs. Knox, Mrs. Strong, Mrs. MacClure and Mrs. Rosborough.’’ However, none of these families, except the McCluers, are mentioned in Justice John’s letter to Hugh’s widow and it is known for certain that the Knoxes and the Rosboroughs came later in the I760’s.

Justice John Gastons and Problems With A Church of England Minister

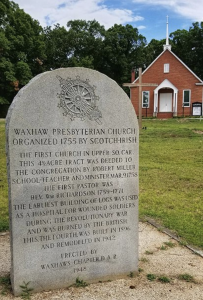

These determined Presbyterians had no sooner got themselves settled and organized in the Fishing Creek congregation of the Reverend William Richardson when a threat to their religion appeared in the person of Charles Woodmason, itinerant Anglican clergyman from Charles Town. Rev. Woodmason was ordained a Priest by the Church of England in 1766. In Northern Ireland, the British had levied a tax for the support of the Episcopal Church on dissenters and Anglicans alike. There was a similar law in South Carolina, but the back-country was too remote for effective enforcement. The Reverend Charles Woodmason, whom some thought insane and others inspired, came resolved to bring the “back people” into “the Church,” — and, incidentally, to have the laws enforced for Anglicanism.

He established himself at Pine Tree Hill (later Camden) in the fall of 1766 and immediately set about to convert or compel dissenters to conformity. His reception fell short of his expectations, and he vented his spleen in his journal: “The people around,” he wrote, “[are] of abandon’d Morals, and profligate Principles — Rude — Ignorant — Void of Manners, Education or Good Breeding.

His first run-in with John Gaston(Lundeen GGP) was in February of 1767. Woodmason rode up to Hanging Rock for preaching on Sunday the 14th. According to his account, he “Found the Houses filled with debauch’d licentious fellows, and Scot Presbyterians who hir’d these lawless Ruffians to insult me. …” He preached anyway. “But the Service was greatly interrupted by a Gang of Presbyterians who kept hallooing and whooping like Indians.

“From this Place I went upwards to Cane Creek where I had wrote to the Church People for to assemble — But when I came I found that all my Letters and Advertisements had been intercepted. I trac’d them into the hands of one John Gaston (Lundeen GGP), an Irish Presbyterian Justice of the Peace on Fishing Creek, on other Side of the River.”

The following fall, Mr. Woodmason’s itinerary brought him into the Waxhaw congregation. The Presbyterians, he said, “looked upon me as a Wolf strayed into Christs fold to devour the Lambs of Grace.” He called on Mr. Richardson but claimed that the minister “denied being at home — Not being willing to give offense to his flock in entertaining a person who was drawing off the People from them.” There were Episcopalians in the vicinity, but, according to Woodmason, they had been deceived by an “Advertisement” stating that he would preach the preceding week, and that a “Multitude” had assembled to no purpose. He therefore “resolved to search into this Presbyterian trick.

When he got back to Pine Tree, he wrote in his journal: “I have unravelled the Mystery of the Advertisement set up at the Waxhaws. ‘Twas done by one John Gaston (Lundeen GGP) a Justice of the Peace among these Presbyterians, to have a Laugh at the Church People,” — which is the only instance on record of a sense of humor on the part of Justice John Gaston.

Another source of discord between the up-country and the coast was the South Carolina law requiring a clergyman for the performance of the marriage ceremony. Across the border in North Carolina, the justices of the peace had this prerogative. Woodmason claimed that many couples whom he united had been living in a state of concubinage for want of a preacher. For understandable reasons. Justice Gaston had taken the law into his own hands. Woodmason was delighted to discover a case against him. In his journal, in 1768, he recorded that John Gaston had “set up to marry People, and has actually married Several Couples, tho’ his own Pastor lives but a few miles from Him [Richardson and Gaston maintaining the most cordial relations despite Woodmason’s efforts.] There is a strict Law against all this — and altho’ I have got Depositions against this Wretch, I can find none to serve. And We are so far from the Supreme Court, as not to be able to obtain Writs from thence, and make Return, within the Time prescrib’d.”

Nevertheless two years later the Anglican clergyman did send a report to Charles Town against Justice Gaston. The Journal of the Governor’s Council contains the following entry for September 4, 1770: His Honor the Lieutenant Governor Communicated to the Board a Letter to Mr. Justice Lowndes from the Rev. Charles Woodmason, Clerk, in which letter Mr. Woodmason complains of John Gaston formerly a Justice of the Peace for taking upon him to Join persons in Matrimony, which Mr. Woodmason alleged was the cause of great disorder in the back Countries, and also an affidavit of one James Adams who was present when the ceremonies was performed by the said Gaston.

The Board thereupon advised his Honor to refer the papers to the Attorney General to form such prosecution on them against the said John Gaston as might be proper on this Occasion. Woodmason was, of course, wrong in describing John Gaston as “formerly a Justice of the Peace” as he had been duly appointed for the years 1769 and 1770. Apparently the Attorney General took the clergyman at his worth and ignored the charges. If Gaston was chastened, it was not for long. During the Revolution he was again uniting the lovelorn, agreeing, no doubt, with St. Paul, that, whatever the circumstances, it was better to marry than to burn.

The up-country had legitimate grievances against the Government in Charles Town on other accounts, also. The coastal counties controlled the legislature by refusing adequate representation to the interior. Even more galling was the failure of the King’s Government to provide law enforcement agencies against roving gangs of frontier thieves. Exasperated back-countrymen, calling themselves Regulators, organized to put down the lawless element. Charles Woodmason came forward as the champion of the Regulators. He cleverly insinuated the establishment of the Episcopal Church as the price of law and order. Few Presbyterians, therefore, joined the Regulator movement, although many of its claims were just. They considered their religion in greater peril than their property. The Regulator leaders became Tories in the Revolution. The Presbyterian leaders were staunchly Whig. Woodmason returned to England in 1776 after a very unsuccessful career.

The struggle of the American colonies for the rights of free men against Great Britain was of intense interest to John Gaston. He had experienced in Ireland the economic and religious intolerance of his Majesty’s Government. If America were to suffer the fate of Ireland, the long voyage to a strange land and the conquest of the wilderness had been made in vain. Differences between up-country and low were of lesser moment. It was Justice John’s custom to send one of his sons weekly to Camden, a distance of fifty miles, to obtain the Charles Town newspaper, there being none published in the interior. By this means, he kept himself and his neighbors informed of British encroachments and made Whigs of his hearers in the telling.

As colonial tempers shortened. South Carolina called a Provincial Congress to meet in Charles Town in 1775 and decide on measures of resistance. In this Congress but few of the up-country leaders were present. The historian M’cCrady explains their absence as a result of the manipulations of low-countrymen to retain their privileged position in politics. Despite the fact that no Americans were more hostile to England than those who had suffered discriminations in northern Ireland, their section of South Carolina was represented by men from the coast. McCrady attributes this to “the work of ‘influential gentlemen’ to whom the writs of election were sent.’’ “It is at least singular,’’ he says, “that we find among the returned none of the Brattons, McLures, Hills, Gastons or Laceys, who so distinguished themselves when the war of the Revolution rolled back to the upper part of the state . . .

No doubt the up-countrymen expected to win representation in their government by fighting the King, for they responded loyally to the call for troops by the Provincial Congress. William Gaston (Lundeen GGP), oldest son of Justice John, was elected Captain of a company of volunteer horsemen for the District between Broad and Catawba Rivers on September 25, 1775. Robert, Hugh and Alexander Gaston (Justice John’s sons) enlisted the same month in the company of Captain Ely Kershaw in Colonel William Thomson’s regiment of Rangers. When the British made their first naval attack on the colonies in June of ’76, seven of the sons of Justice Gaston were in Charlestown to repel it.’’ On the morning of June 28, 1776 nine British warships, commanded by Commodore Sir Peter Parker, attacked the incomplete fort on Sullivan’s Island. Armed with only 31 cannons, Moultrie’s command faced over 270 British cannons. The fort’s palmetto log and sand walls absorbed much of the British fire and suffered little damage. After over nine hours of combat, the British fleet was defeated. The Battle of Sullivan’s Island ended in a decisive Patriot victory. The victory at Fort Moultrie won a respite for South Carolina until the invasion of ’79 and ’80. For the intervening years, there was comparative peace in the state.

Several of the Gastons continued to serve in the Rangers of “Old Danger” Thomson, Captain Kershaw’s company, for the next three years. Alexander Gaston (Justice John’s Son) rose to the rank of lieutenant, the only member of the family to win a commission in the Continental service. The other brothers fought with the militia in such companies as those of their brother Captain William (Justice John’s Son–Lundeen GGP) or their cousin Captain John McClure. These were followers of the “Gamecock,” General Thomas Sumter. “Encouraged by the Councils of a Patriotic Father,” wrote Joseph Gaston (youngest son of Justice John Gaston), all nine of the brothers were eventually “engaged in that Bloody conflict.”

The darkest day for South Carolina came on May 12, 1780, when the American forces were compelled to surrender Charlestown to the British. Captain John McClure had led a company of mounted militia to aid in defending the capital but arrived too late and escaped capture. The state was now a conquered province and the Redcoats moved inland to wipe out resistance and to offer “protection” to such as would lay down their arms and promise to remain loyal subjects of the King.

The sons and nephews of Justice Gaston frequently met at his home to confer on issues of the war and local strategy. Captain John McClure on his return from Charlestown stopped at his uncle’s house. While he was there a messenger arrived with news of Tarleton’s massacre of Buford’s men near the Waxhaws. Though the Americans had thrown down their arms and called for quarter, they were slaughtered without mercy. This was only twenty miles distance from Cedar Shoals where the Gaston’s lived.

“On the reception of this news,” wrote Joseph Gaston (youngest son of Justice John), then a youth of seventeen, “he (Captain John McClure) and three of the said Gaston’s sons, and Captain John Steele, arose upon their feet and made this united and solemn declaration, ‘that they would never submit nor surrender to the enemies of their country; that liberty or death from that time forth should be their motto.’

The Gaston women were nothing behind their men in patriotism. The youngest daughter, Esther, then about nineteen, “tall and well developed in person and possessed of great mental and physical energy” made her own private vow to aid her country and became one of the most notable heroines of the Revolution. Esther Gaston’s story and that of her family are recounted from the reports of participants in Mrs. Ellet’s Women of the Revolution, Few of Mrs. Ellet’s original sources are extant, but her retelling, in somewhat heroic vein, is perhaps not inappropriate to the events related:

The wounded from Buford’s massacre had been taken to the Waxhaw church as a hospital. Esther Gaston went immediately as a nurse, “accompanied by her married sister Martha Gaston, and Martha’s son John, a boy eight years of age. The temporary hospital presented a scene of misery. The floor was strewed with the wounded and dying American soldiers, suffering for want of aid; for men dared not come to minister to their wants. It was the part of woman, like the angel of mercy, to bring relief to the helpless and perishing. Day and night they were busied in aiding the surgeon to dress their wounds, and in preparing food for those who needed it; nor did they regard fatigue or exposure, going from place to place about the neighborhood to procure such articles as were desirable to alleviate the pain, or add to the comfort, of those to whom they ministered.

“Meanwhile, the British were taking measures to secure their conquest by establishing military posts throughout the State. Rocky Mount was selected as a stronghold, and a body of the royal forces was there stationed. Handbills were then circulated, notifying the inhabitants of the country that they were required to assemble at an old field, where Beckhamville now stands, to give in their names as loyal subjects of King George, and receive British protection. After this proclamation was issued. Col. Houseman, the commander of the post at Rocky Mount, was seen with an escort wending his way to the residence of old Justice Gaston. He was met on the road by the old man, who civilly invited him into the house. The subject of his errand was presently introduced, and the Justice took the opportunity to animadvert, with all the warmth of his feelings, upon the recent horrible butchery of Buford’s men, and the course pursued by the British government towards the American Colonies, which had at length driven them into the assertion of their independence. In despair of bringing to submission so strenuous an advocate of freedom. Col. Houseman at last left the house; but presently returning, he again urged the matter. He had learned, he said, from some of His Majesty’s faithful subjects about Rocky Mount that Gaston’s influence would control the whole county; he observed that resistance was useless, as the province lay at the mercy of the conqueror, and that true patriotism should induce the Justice to reconsider his determination, and by his example persuade his sons and numerous connections to submit to lawful authority, and join the assembly on the morrow at the old field. To these persuasions the old man gave only the stern reply—‘Never!’

“No sooner had Houseman departed, than the aged patriot took steps to do more than oppose his passive refusal to his propositions. He immediately dispatched runners to various places in the neighborhood, requiring the people to meet that night at his residence. The summons was obeyed. Before midnight, thirty-three men, of no ordinary mould, strong in spirit and of active and powerful frames — men trained and used to the chase — were assembled. They had been collected by John McClure, and were under his command. Armed with the deadly rifle, clad in their hunting shirts and moccasins, with their wool hats and deer¬ skin caps, the otter-skin shot-bag and the butcher’s knife by their sides, they were ready for any enterprise in the cause of liberty. At reveille in the morning, they paraded before the door of Justice Gaston. He came forth, and in compliance with the custom of that day, brought with him a large case bottle. Commencing with the officers, John and Hugh McClure, he gave each a hearty shake of the hand, and then presented the bottle. In that grasp it might well seem that a portion of his own courageous spirit was communicated, strengthening those true hearted men for the approaching struggle. They took their course noiselessly along the old Indian trail down Fishing Creek, to the old field where many the people were already gathered. Their sudden onset took by surprise the promiscuous assemblage, about two hundred in number; the enemy was defeated, and their well directed fire, says one who speaks from personal knowledge, ‘saved a few cowards from becoming tories, and taught Houseman that the strong log houses of Rocky Mount were by far the safest for his myrmidons.’

“This encounter was the first effort to breast the storm after the suspension of military opposition; ‘the opening wedge,’ in the words of an eye witness, ‘to the recovery of South Carolina.’ Before the evening of that day, Justice Gaston was informed of the success of the enterprise, and judging wisely that his own safety depended on his immediate departure, his horse was presently at the door, with holster and pistols at the pommel of the saddle. The shot-bag at the old man’s side was well supplied with ammunition, and his rifle, doubly charged, lay across the horse before him. Bidding adieu to his wife and grandchildren, and bestowing on them his parting blessing, he left home with his young son, Joseph, who was armed and mounted on another horse. On his way he made a visit to Waxhaw church, where his daughters Esther and Martha were still occupied with their labor of kindness, to carry the news that ‘the boys,’ as he called them, had done something towards avenging the injuries of the poor men who were dependent on their care. A shout of exultation from the women welcomed the intelligence, and many a wounded soldier felt his sufferings mitigated by the tidings. The Justice pursued his way till he could consider himself beyond the danger of pursuit. His son Joseph returned, and marching with a detachment of men from Mecklenburg, North Carolina, in a few days joined his brothers in arms under the gallant John McClure.

“Loud and long were the curses of Houseman levelled against old John Gaston. The arch rebel, he declared, must be taken, dead or alive, and the king’s loyal subjects were called upon to volunteer in the exploit of capturing and bringing to Rocky Mount a hoary headed man, past seventy years of age. for the crime of being the friend of his country and bringing nine sons into the field. Before the sun rose, about twenty redcoats were fording Rocky Creek, and wending their way along the Indian trail leading to Gaston’s house. The thirst for revenge rankled in their hearts, and destruction and murder were in their purpose; but the God who protects those who place reliance on Him in all trial and danger, had opened a way of escape for the patriot’s family. His wife and little Jenny, the daughter of his son William Gaston, providentially advised of the enemy’s approach, had quitted the house.

In her flight, Mrs. Gaston (Lundeen GGP) carried her family Bible in her apron, and with her motherless grand-daughter hid near enough to the house to hear the British and Tories as they ransacked her home and premises. The soldiers hacked the chairs with their broadswords, tore open the beds and broke the glassware. They sliced up the books, among them some valuable volumes and the family Bible of the Reverend Hugh Gaston, and scattered his manuscript sermons on the floor. The house was plundered of everything of value and the stock carried off.

Mrs. Gaston (Lundeen GGP) spent much of her time of concealment in prayer. In the fervor of her supplication, she prayed aloud. Little Jane in telling the story years afterwards remembered that her grandmother became so audible in her communion with the Diety that she all but gave away their hiding place to the marauders.

The night following the raid, Mrs. Gaston and her grandchildren took refuge in the home of Thomas and Jane Gaston

Walker, parents of Alexander Walker who later married Esther Gaston. Of their personal belongings, the Gastons’ family Bible alone escaped undamaged. The bare walls of their home and their lands were all that remained of over twenty years’ labor and saving.

Captain John McClure’s small force was the only protection available to the patriots. After the success of their rally at Beckhamsville, these partisans, says Joseph Gaston, “then rushed to another collection of tories, of still worse materials, at Mobley’s meeting-house in Fairfield, where the tories suffered much. A number were killed! The intrepid movements of this little band surprised them like a peal of thunder from a clear sky.” The victories of McClure’s men attracted others to his standard. The band shortly joined Thomas Sumter, recently commissioned General by Governor Rutledge, and “formed the nucleus of his army.” They were next engaged against Captain Christian Huyck of the green-coat New York Tories at Williamson’s Plantation (now Brattonsville). Captain Huyck “who never failed, on convenient occasions, to curse Bibles and Presbyterians,” according to Joseph Gaston, was slain on the morning of July 12, 1780, along with a number of his Tories. The Whigs did not lose a man, killed or wounded.

Two weeks later, Sumter planned an attack on the British at Rocky Mount. When his troops marched near the residence of Justice Gaston, Joseph the youngest of the sons, joined his brothers and cousins in arms. Esther Gaston learned the destination of the expedition and made ready again to help where she could. She rode about two miles to the home of her brother John Gaston Jr. and urged his wife Jannet’’ to go with her to the scene of action. “The two were soon mounted, and making their way at a quick gallop down the Rocky Mount road. The firing could be distinctly heard. While these brave women were approaching the spot, they were met by two or three men, hastening from the ground, with faces paler than became heroes. Esther stopped the fugitives, upbraided them for their cowardice, and entreated them to return to their duty. While they wavered, she advanced, and seizing one of their guns, cried ‘Give us your guns, then, and we will stand in your places!’ The most cowardly of men must have been moved by such a taunt …. Wheeling about, they returned to the fight in company with the two heroines.

The Whigs attacked for a good part of the day at Rocky Mount, but, wrote Joseph Gaston, “without making much impression on Col. Turnbull, he being stationed in a strong log house. Esther and Jannet carried water, dressed wounds, and comforted the dying, among them a Catawba Indian who fought with the Americans.

06 Aug., 1780 Hanging Rock Battlesight, 2.5 mile S. of Heath Springs, Lancaster Co., South Carolina, USA

The “Battle of Hanging Rock” – Revolutionary War – was fought at this site 06 Aug., 1780. The Army of Gen. Sumpter of 500 North Carolina & 300 South Carolina Patriot Militia marched 16 miles during the night & attacked the 1400 British & Tory Army & Militia at dawn. The battle lasted 4 hours. Many participants fainted due to lack of water & dehydration during the battle. The British were defeated. The landscape was made up of steep hills littered with huge rounded bolders. The rock at the top of this picture has a cut out sheltered area that is covered by the top part of the rock. This was a British Camp-sight. – at the rt. lower picture is a monument about the Battle.

The battle of Hanging Rock which followed was the costliest in the annals of the South Carolina Gastons. On August 6, 1780, General Sumter, with militia from both Carolinas, fell upon the British and Tories encamped near the immense boulder in the present Lancaster County. The main attack centered on the Tories under Colonel Bryan. John McClure, having recently been elected Colonel of the Rocky Creek and Fishing Creek troops, held a front line command and his men sustained much of the enemy’s first fire. Though hit in the thigh, McClure continued to lead his men. Justice John’s sons Robert, David and Ebenezer were killed, one falling dead across another and the third mortally wounded. Joseph, though scarcely more than a boy, advanced across the bodies of his brothers to the front. A rifle ball struck him in the face, grazed his nose and knocked off the top of his cheekbone. Recounting the battle later, he said he was conscious of taking aim at a man and pulling the trigger the moment he was shot. The ball cut through his cheekbone, tearing a hole more than twice its size. Faint from loss of blood, he was carried to a stream in the rear. With other wounded survivors, he was taken to Waxhaw church where his sisters Esther and Martha were among those dressing wounds. Only Buford’s Massacre equalled Hanging Rock in carnage. Dr. James Knox, son of Elizabeth Gaston, performed valiant service as surgeon. Mary Gaston McClure came to nurse her fallen son who died afterwards when the wounded were taken to Charlotte. Andrew Jackson, who fought with Sumter at Hanging Rock, is said to have gained his idea of war from the harvest of the battlefield gathered in Waxhaw church.

A poem to John McClure written by Dr. Richard Wylie of Lancaster who knew many of the survivors of Hanging Rock

contains these verses:

Though in their ranks red carnage stood ..Nought could their courage quell… Three Gastons dying, mingled blood… A fourth one wounded fell… His cheek was shattered ere he sunk… By which good mark we know… A Gaston nere turned back nor shrunk… Before his country’s foe.

Joseph Gaston was proud of his wound with his face toward the enemy and held it a mark of distinction. For many years it was painful and ulcerating and it left his nose disfigured and his cheekbone flat. It did not, however, keep him long from the field. By November 20, he was back with the Gamecock and fought in the battle at Blackstocks. Following that, he was smitten with a violent case of small-pox, and his life hung in the balance for weeks. But before the war’s end, he was again in the ranks.

The levy of Gaston blood was not yet completed. After the early defense of Charles Town, young Alexander Gaston, whom had become a lieutenant in the regular army, returned home with his friend Lieutenant William Grey to the present Fairfield County. During the peaceful interlude, he became engaged to William’s sister Mary. It is recorded of the young men that “both of them were fond of the pomp and show of war. Their uniforms were splendid and rich in material, their three cornered hats, plumed with feathers, moved high above their heads. When the regulars made the gallant charge on the British at Savannah, Gaston was wounded. The remarks of the soldiers of the Revolution were that his uniform made him too conspicuous. When the campaign of ’80 opened, these two young lieutenants were again in the field.” They escaped capture at the fall of Charles Town and returned to the up-country and joined Thomas Sumter. The Gamecock led a force to the low-country early in ’81. At Wright’s Bluff on Black River, Sumter encountered a body of British and Tories on February 27. These proving too numerous, he was forced to retreat across the river. Lieutenant Gaston had contracted small-pox and getting wet in the crossing became too ill to move on. He was taken to the home of a McConnell family; and there, far from Cedar Shoals and his family, the youthful officer died in a few days. The uniform of which he had been so proud was obtained by his family and carefully preserved.

Mrs. Esther Gaston (Lundeen GGP) received the news of the deaths of her sons with Spartan courage and Christian faith. “I grieve for their loss,” she said, “but they could not have died in a better cause.

On his enforced flight from Cedar Shoals, Justice John(Lundeen GGP) had intended to go to New Bern, N. C., to the home of his brother, Dr. Alexander Gaston. He had found his way blocked by the Loyalists at Cross Creek and turning back had remained a few weeks in Iredell and Mecklenburg Counties. On learning of the Battle of Hanging Rock, he returned home, observing that it was at best but a few days of life that could be taken by his foes. He found his home a place of grief and destruction, destitute even of a bed. He and his wife were compelled to sleep on cowhides stretched on the floor. Reprisals were too menacing to permit even the luxury of mourning for their lost sons. The Justice went armed with a brace of horseman’s pistols and his trusty rifle, resolved in case of attack “to defend to the death his home and aged partner.” The victories of the Whigs, however, were a check on those disposed to molest him, and the only hostile demonstration was the cutting out of his initials from a white oak on the road to his home.

Had he succeeded in reaching New Bern, he would have discovered there only bloodshed and heartbreak equal to that at Cedar Shoals. Before the war, Dr. Alexander Gaston had prospered in his profession and become a prominent citizen of the North Carolina town. His wife, Margaret Sharpe, and small children born during the war had made a happy home. From the outbreak of hostilities, he had been an active Whig. The details of his murder by the Tories, on August 20, 1781, are told in the words of his son, Judge William Gaston. “I have so often heard them stated by my weeping mother,” said the Judge, “that I can never forget them.”

“Dr. Gaston was one of those who were peculiarly obnoxious to the Tories, and it was deemed advisable for all such to keep out of the way of their ferocity. He had retired to his plantation on the South side of Trent, but misled by some information respecting the movements of the detachment, he returned to town on Saturday, and stayed with his family until after breakfast the next day. Rumors of the approach of the Tories, joined with the entreaties of Mrs. Gaston induced him then to revisit his plantation. He had quitted his house (which stood on the spot where the Bank of New Bern now stands) but a short time, when the mounted men, who consisted entirely of Tories, under the command of Captain Cox, and formed the advance of the detachment, galloped into town, and proceeded directly to the wharves. Mrs. Gaston, fearful that her husband might not have crossed the ferry, and unable to endure the agonies of suspense, rushed down the street to the Old County Wharf, and found them actually firing at him. He was in the ferry boat, at a very short distance from the shore, and alone, the boy who had been rowing the boat having jumped over board. She threw herself between him and the assailants, and on her knees, with all a woman’s eloquence, implored them to spare the life of her husband. The captain of the savage band answered these cries by damning him for a ‘rebel’ and his followers as ‘blunderers,’ called for a rifle, levelled it over her shoulder and stretched him a corpse.”

The Revolutionary services and sacrifices of other members of the wide Gaston connection are told in the third volume of Mrs. Ellet’s Women of the Revolution. It is a record with few parallels in American history. There was no “taking protection” for the preservation of persons and property. For both able bodied and infirm, it was “Liberty or Death” until independence was won.

Justice John Gaston (Lundeen GGP) did not survive the war. He died in 1782, “his pistols being still under his pillow and his rifle beside him.” His exact age is not known. According to tradition, he was eighty-two; but available evidence indicates that he was in his early seventies. He was buried in lower Fishing Creek churchyard (known as Richardson’s for its first pastor) by the side of his brother, the Reverend Hugh Gaston. In this church. Justice John had been a ruling elder, and established thereby a Presbyterian precedent followed by his descendants for two centuries in Chester.

Esther Waugh Gaston (Lundeen GGP) survived her husband for seven years and died in 1789. One daughter and four sons preceded her to the grave. Her youngest son, Joseph, did not marry until after her death and lived with her at Cedar Shoals as did several of the grandchildren. In the same county (Chester was created in 1785) lived her two daughters, Martha with her husband Joseph Gaston (a distant cousin), and Esther with her husband Alexander Walker (son of Jane Gaston Walker), and their children. In Chester, also, lived her sons: Captain William with his second wife Ann (Lundeen GGP’s); John and Jannet; James and Margaret; Hugh and Martha (who were first cousins) and the large families of each. None of the children of Mrs. Gaston moved south or west until after her death.

In the twentieth century. Justice Gaston and his family became heroes and heroines of fiction in the historical novel Polly of the Pines, by Adele E. Thompson, an Ohio authoress. In North Carolina, Gaston County and the city of Gastonia were named for Dr. Alexander Gaston’s son, Judge William.

CHILDREN OF JUSTICE JOHN AND ESTHER WAUGH GASTON

- Margaret Gaston: August 29, 1739 – 1767 Married James McCreary.

- Martha Gaston: June 11, 1741 – March 4, 1826. Married Joseph Gaston, d. April 21, 1823 aged 84 Will (Joseph) lists sons Alexander and John, and daughters Martha, Margaret, Esther and Jane. Buried in Upper Fishing Creek churchyard, Chester County.

- William A. Gaston: June 5, 1743 – 1814. Married 1st Jeannette Love then 2nd Ann Porter (GGP)

Will lists sons William and James, daughters Kesiah, Ann, Susanna, Martha, Elizabeth, and Esther Akien (Lundeen GGP), Margaret

Hoskins, Jane Davis. (daughter from previous marriage with Jeanette Love)

- John Gaston: June 24, 1745 – January, 1808.

Married Jannet Knox in Fall of 1768……Will lists sons William and James, daughter Esther…Widow died in Illinois.

- James Gaston: April 15, 1747 –

Married Margaret…Had son Stephen and number of daughters…Moved to Tennessee and Indiana Territory.

- Robert Gaston: March 11, 1749 – August 7, 1780

Killed at Hanging Rock.

- Hugh Gaston: March 12, 1751 – June 13, 1836

Married Martha McClure, d. December 21, 1836, aged 82…Sons: John, Ebenezer, James, William, Hugh…Daughters: Mary, Martha, Esther, Margaret

Buried in Shell Creek Cemetery, Wilcox County, Ala.

- Alexander Gaston: August 24, 1753 – 1781

Died of smallpox after battle of Wright’s Bluff.

- David Gaston: July 7, 1755 – August 7, 1780.

Killed at Hanging Rock.

- Ebenezer Gaston: September 15, 1757 – August 7, 1780

Killed at Hanging Rock.

- Esther Gaston: October 15, 1760 – 1809

Married Alexander Walker.

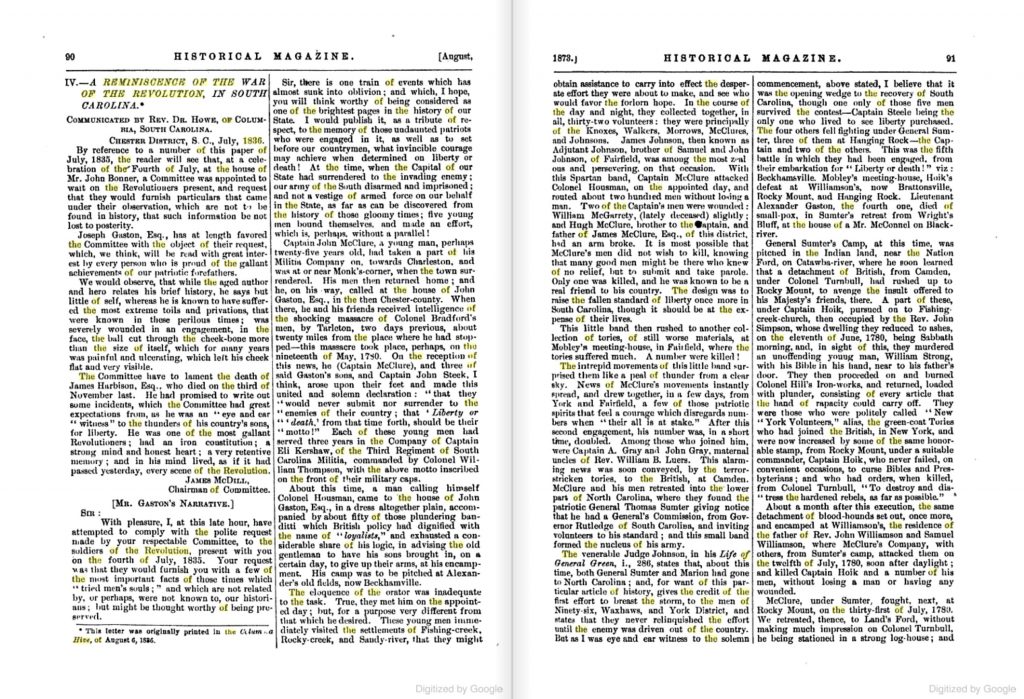

A Reminiscence Of The Revolution- By Joseph Gaston

Copy of Article from the Columbia Hive, August 6, 1836 Chester District So. Carolina

July 1836

By reference to a number of this paper of July, 1835, the reader will see, that at a celebration of the 4th July, at the house of Mr. John Bonner, a committee was appointed to wait on the Revolutioners present, and request, that they would furnish particulars that came under their observation, which are not found in history, that such information be not lost to posterity. Joseph Gaston, Esq. has at length favored the Committee with the object of their request, which, we think, will be read with great interest by every person who is proud of the gallant achievements of our patriotic forefathers. We would observe, that while the aged author and heir relates his brief history, he says but little of self, whereas he is known to have suffered the most extreme toils and privations, that were known in these perilous times—was severely wounded in an engagement, in the face, the ball cut through the cheek bone more than the size of itself, which for many years was painful and ulcerating, which left his cheek flat and very visible. The Committee have to lament the death of James Harbison, Esq., who died on the 3rd of November last. He had promised to write out some incidents, which the Committee had great expectations from, as he was an “eye and ear witness” to the thunders of his Country’s sons for liberty. He was one of the most gallant Revolutioners, had an iron constitution, a strong mind, an honest heart, a very retentive memory, and in his mind held, as if it had passed yesterday, every scene of the Revolution.

James McDill…Chairman of Committee

Sir, with pleasure, I, at this late hour, have attempted to comply with the polite request made by your respectable committee, to the Soldiers of the Revolution, present with you on the 4th July, 1835. Your request was that they would furnish you with a few of the most important facts of those times which “tried men’s souls;” and which are not related by, or perhaps, were not known to our historians; but might be thought worthy of being preserved. Sir, there is one train of events which has almost sunk into oblivion; and which, I hope, you will think worthy of being considered as one of the brightest pages in the history of our State.

I would publish it as a tribute of respect to the memory of those undaunted patriots who were engaged in it as well as to set before our countrymen, what invincible courage may achieve when determined on liberty or death. At the time, when the capital of our State had surrendered to the invading enemy; our army of the South disarmed, and imprisoned, and not a vestige of armed force on our behalf in the State (as far as can be discovered from the history of those gloomy times), five young men bound themselves, and made an effort, which is, perhaps, without a parallel!

Captain John McClure, a young man, perhaps twenty-five years old, had taken a part of his militia company on towards Charleston and was at or near Monk’s Corner when the town surrendered. His men then returned home; and he, on his way, called at the house of John Gaston, Esq., in the then Chester County. When there, he and his friends received intelligence of the shocking massacre of Colonel Buford’s men by Tarlton, two days previous, about twenty miles from the place where he had stopped. (This massacre took place perhaps on the 19th of May, 1780). [McCrady dates Buford’s massacre as May 29, 1780.]. On the reception of this news, he (Captain McClure) and three of said Gaston’s sons, and Captain John Steele, I think, arose upon their feet and made this united and solemn declaration, “that they would never submit nor surrender to the enemies of their country; that liberty or death from that time forth, should be their motto”! Each of these young men had served three years in the company of Captain Eli Kershaw, of the third Regiment of South Carolina Militia, commanded by Col. Wm. Thompson with the above motto inscribed on the front of their military caps. About this time a man calling himself Col. Houseman, came to the house of John Gaston, Esq., in a dress altogether plain, accompanied by about fifty of those plundering banditti, which British policy had dignified with the name of loyalists and exhausted a considerable share of his logic in advising the old gentleman to have his sons brought on a certain day to give up their arms at his encampment. (His camp was to be pitched at Alexander’s old fields, now Beckhamville). The eloquence of the orator was inadequate to the task. True, they met him on the appointed day; but for a purpose very different from that which he desired. These young men immediately visited the settlements of Fishing Creek, Rocky Creek, and Sandy River, that they might obtain assistance to carry into effect the desperate effort they were about to make; and see who would favor the forlorn hope. In the course of the night they collected together, in all thirty-two volunteers: they were principally of the Knoxes, Walkers, Marrows, McClures and Johnsons. James Johnson, then known as Adjutant Johnson brother of Samuel and John Johnson of Eairfield, was among the most zealous and perseverent on that occasion. With this Spartan band Captain McClure attacked Col. Houseman, on the appointed day, and routed about two-hundred men, without losing a man; Two of the Captain’s men were wounded: Wm. McGarrety slightly; Hugh McClure, brother to the Captain, and father of James McClure, Esq., of this district had an arm broke. It is most possible that McClure’s men did not wish to kill, knowing that many good men might be there who knew of no relief but to submit and take parole. Only one was killed, and he was known to be a real friend to his country. The design was to raise the fallen standard of liberty once more in South Carolina, though it should be at the expense of their lives. This little band then rushed to another collection of tories, of still worse materials, at Mobley’s meeting-house in Fairfeld, where the tories suffered much. A number were killed! The intrepid movements of this little band surprised them like a peal of thunder from a clear sky. News of McClure’s movements instantly spread, and drew together in a few days from York and Fairfield a few of those patriotic spirits that feel a courage which disregards numbers when “their all is a stake.’’ After this second engagement, his number was, in a short time doubled. Among those who joined him, were Captain Gray and John Gray maternal uncles of Rev. Wm. B. Luers. [ ? ] This alarming news was soon conveyed, by the terror stricken tories, to the British at Camden. McClure and his men retreated into the lower part of North Carolina, where they found the patriotic General Thomas Sumter, giving notice that he had a General’s commission from Governor Rutledge of South Carolina; and inviting volunteers to his standard; and this small band formed the nucleus of his army. The venerable Judge Johnson, in his life of General Green, Page No. 286, V. 1, states that about this time both Generals Sumter and Marion had gone to North Carolina, and for want of this particular article of history, gives the credit of the first effort to breast the storm to the men of Ninety-six, Waxhaws, and York district; and states that they never relinquished the effort until the enemy was driven out of the country. But as I was an eye and ear witness to the solemn commencement above stated, I believe that it was the opening wedge to the recovery of South Carolina, though one only of those five men survived the contest—Captain Steele being the only one who lived to see liberty purchased.

The four other Gaston brothers fell fighting under General Sumter, three of them at Hanging Rock, (the Captain and two of the others) . This was the fifth battle in which they had engaged, from their embarkation for liberty or death! viz: Beckham’sville, Mobley’s meeting-house, Hoik’s defeat at Williamson’s (now Brattonville), Rocky Mount and Hanging Rock.

Lieut. Alexander Gaston, the fourth one, died of small pox, in Sumter’s retreat from Wright’s Bluff, at the house of a Mr. McConnell on Black River. General Sumter’s camp, at this time, was pitched in the Indian land, near the Nation ford on Catawba River, where he soon learned that a detachment of British, from Camden, under Col. Turnbull had pushed up to Rocky Mount to avenge the insult offered to his Majesty’s friends there. A part of these, under Captain Hoik, pursued on to Fishing Creek church, then occupied by the Rev. John Simpson, whose dwelling they reduced to ashes on the 11th of June, 1780, (being Sabbath morning) and in sight of this they murdered an unoffending young man (Wm Strong), with his bible in his hand, near to his father’s door. They then proceeded on and burned Col. Hill’s iron Works, and returned loaded with plunder, consisting of every article the hand of rapacity could carry off. They were those who were politely called the New York Volunteers, alias the green-coat tories who had joined the British in New York, and were now increased by some of the same honorable stamp from Rocky Mount under a suitable commander. Captain Hoik, who never failed, on convenient occasions, to curse Bibles and Presbyterians, and who had orders when killed, from Col. Turnbull, “To destroy and distress the hardened rebels as far as possible.’’ About a month after this execution, the same detachment of blood-hounds set out once more and encamped at Williamson’s, the residence of the father of Rev. John Williamson and Samuel Williamson, where McClure’s company with others from Sumter’s camp attacked them on the 12th of July, 1780, soon after daylight, killed Captain Hoik and a number of his men without losing a man or having any wounded. McClure, under Sumter, fought next at Rocky Mount, on 31st July, 1780. We retreated thence to Land’s Ford, without making much impression on Col. Turnbull, he being stationed in a strong log house; and while at Land’s Ford, General Sumter ordered an election for general officers in the Chester Regiment. McClure’s company that day numbered about one hundred and twenty men. He was elected Colonel. Major John Nixon, father of Mrs. McKeown and Mrs. Hemphill, widow of Rev. J. Hemphill, was elected Lieut. Colonel—Colonel E. Lacy having at that time, become unpopular among the Chester Whigs. From Land’s Ford, General Sumter marched to Hanging Rock on the 7th of August, 1780, where we (the writer having joined McClure’s company) attacked a tory camp of seven or eight hundred men, mostly riflemen, hunters from the forks of Yadkin River, under the command of Colonel Morgan Bryant. From that post the Brittish lay about a quarter of a mile. Our force, I think, was not more than four hundred men. Our order of battle was in three lines, about one hundred apart in files of two. The enemy’s lines were extended from a point at right angles. McClure commanded the front of the centre line, against the united point of the enemy’s line; and, on this account, sustained much of the enemy’s first fire. The loss of our men, in the action, was twenty-three, nine of those were of McClure’s company, he being one of the nine, and nine more wounded who recovered. The Captain, and perhaps three others, lived a few days after the battle.

I had been detached to go with my aged father, that he might be removed from the tories who sought his life, for being the friend of his oppressed country as well as for bringing nine sons into the field for its defense. He was disappointed by the tories on Cross Creek, of getting to a brother’s, in Newbern,No Carolina, a Dr. Alexander Gaston, who was killed by the Brittish about this time. We then took a different rout. On my return, I marched with a detachment of men from Mecklenburg, N. C., and think the heroic patriotism of an old lady, on that occasion worth recording. A Mrs. Haynes of that County, as her son was about to leave the door and domestic circle, for the camp, as her parting counsel to him said, “Now Alexander, fight like a man, and don’t be a coward.’’ This I had from an eye and ear witness. We joined General Sumter in the time of the engagement at Rocky Mount, and not long after our arrival I met young Haynes coming out of the fight, with satisfactory proof that he had obeyed the injunctions of his patriotic mother a ball having passed through his face, of this however, he recovered, with the loss of an eye.

A Mr. Robert Walker, the maternal grandfather of R. W. Gill and E. Gill, late of Lancasterville in this State, when engaged in the battle of Kings’ Mountain, during the desperate effort made there by both parties, of advancing and retreating, was shot through the body, near the heart, by one in his view; and having his gun loaded at the time, he after this took deliberate aim and shot his opponent dead. He survived, and many heard him and his officer. Col. E. Lacy, relate this fact.

N.B. I beg leave to mention that Captain John McClure was a younger brother of the late General Wm. McClure, of

Newbern, N. C., who endeared himself so much to our sick and wounded in Charleston, during and after the siege of that place, by his medical assistance to them.

I added two anecdotes by way of conclusion because I considered them well worth inserting.

With most sincere respect, I am yours,

Joseph Gaston. June 28th, 1836.

Also published in [Dawson’s] Historical Magazine

[Morrisania], N. Y., Vol. II, Third Series, August, 1873,

- 90-92.

Notes For Prologue and Sources for Historical Information

NOTES FOR PROLOGUE

- Conversations of Joseph Gaston with Daniel G. Stinson and Jane Gaston Crawford, quoted in The Gaston Family (Murfreesboro, Tenn., ca. 1887), a pamphlet published by William Ramson from notes obtained from Mrs. J. S. Wilson who took them down from Daniel G. Stinson and

others. This pamphlet was later reprinted, in abridged form, by Judge George W. Gage (husband of Janie Gaston) of Chester, S. C.

- Retold from general French histories by Mildred Welch, Let Him Who Loves Me Follow Me, undated leaflet.

- The Gaston Family, passim. John O’Hart, Irish Pedigrees, II (Dublin, 1888), 463 and 478, lists the name Gaston as among the foreign refugees who settled in Great Britain in the reign of Louis XIV (1643-1715) and as among the Huguenots naturalized in Great Britain between 1681 and 1712.

- Charles A. Hanna, Ohio Valley Genealogies (New York, 1900), 40. A memorial of William Gaston from the City of Boston (Boston, 1895), 40, states that “William [was] born about 1680 at Caranleigh, Cloughwater, where he lived all his days, and died in the year 1770; and the other two sons [father’s name not given] Alexander and John, came to America.” This John Gaston was the great grandfather of Governor William Gaston of

Massachusetts.

NOTES FOR THE FIRST GENERATION

- The Gaston Family (Murfreesboro, Tenn., ca. 1887) states that John married Esther in Ireland, came first to Pennsylvania and to South Carolina about 1751-52. Mrs. Elizabeth F. Ellet, The Women of the Revolution, III (New York, 1852), 155, states that John married Esther in Pennsylvania in 1730 but this is obviously an error. In “A General Return of Colo. Thomson’s Regiment of Rangers,”

- C. Historical and Genealogical Magazine, II, 178, the birthplace of Hugh, Robert, and Alexander Gaston is given as Ireland. These can be identified as the sons of John Gaston by their ages and by the company. However, Hugh Gaston in his pension papers says “I was born as I believe in the state of Pennsylvania or New Jersey March 12, 1751″ (File SIO 729, General Services Administration, National Archives, Washington, D. C.)

Esther Gaston is recorded in Mrs. Ellet, III, 156, as having been born at Cedar Shoals in 1761. The Gaston family Bible gives her birth date as 1760. This Bible, published in Dublin, Ireland, in 1754, came down to Jane Gaston Crawford, grand-daughter of Justice John Gaston, and was given by her to her grand-daughter Mrs. Irene Peden who gave it to Mrs. James Ragsdale, Columbia, S. C.

- Mrs. Ellet, III, 156.

- James Gaston, third son of Justice John, sold land on Fishing Creek containing the place called Cedar Shoals to Alexander Walker in 1803. James had been willed the land by his father. He, James, described himself in 1803 as of Smith County, Tenn. His wife, Margaret, renounced her dower rights in the deed. His son Stephen and nephew John Gaston Walker witnessed the deed. In 1811, James sold the rest of his Chester lands. He was

then of Springfield township, Indiana Territory. Chester County Deed Books J. and P., Chester, S. C.

- Dudley Jones, History of Purity Presbyterian Church (Charlotte, 1938), 16-17. The will of James McCluer, made 1769, proved 1771, is in Wills 1767-71, Probate Court, Charleston, S. C. His children spelled the name McClure.

- Mrs. Ellet, III, 170; Edward McCrady, Jr., “Colonial Education in South Carolina,” in Colyer Meriwether, History of Higher Education in South Carolina (Washington, 1889), 226-27.

- Mrs. Ellet, III, 156. The earliest record of John Gaston as a surveyor is in the MS. S.C. Council Journal 1763-64, No. 30, p. 210 (date 1764) in the S.C. Historical Commission, Columbia, S. C.

- MS. S.C. Council Journal 1763-64. No. 30, p. 218, S. C. Historical Commission, Columbia, S. C.

- Robert L. Meriwether, The Expansion of South Carolina (Kingsport, 1940), 180; Edson L. Whitney, The Government of the Colony of South Carolina (Baltimore, 1895), 80.

- The South Carolina Gazette (Charlestown, S. C.), lists the justices of the peace by counties in issues for Oct. 19-31, 1765; Oct. 12-19, 1767; Oct. 18, 1769; Oct. 18, 1770. Wells Register and Almanac for 1774 lists John Gaston as a justice for Camden District as does the S.C, Gazette for January 23, 1775. Both John and William Gaston are listed as justices for Camden District in the S.C. Gazette and Am. General Gazette, April 10-17,

1776, confirmed by A. S. Salley, ed.. Journal of the General Assembly (Columbia, 1906), 20. Mrs. Ellet, III, 156.

- This estimate is based on lands mentioned in the Will of John Gaston, made April 18, 1782, in Chester, S.C., courthouse, and on the division of the estate of Joseph Gaston, who inherited his father’s resident plantation (D. G and Esther Stinson to James A. H. Gaston, July 23, 1840, Deed Book CC, p. 341) and other deeds Book CC, p. 524, Book DD, p. 444.

- Conversations with Mrs. Thomas Peden (Irene McCreary) 1849-1941, who was born at her grandmother’s (Jane Gaston Barkley Crawford, daughter of Joseph Gaston) and lived near her until her death in 1880, aged 80. Mrs. Crawford lived in the old homestead of her father Joseph and grandfather Justice John.

- Daniel G. Stinson, “Susan Smart,” Palmetto Standard (Chester, S. C.), October 1, 1851.

- MS. Genealogy of the Gaston Family in the papers of Mrs. Dick (?) Daly of Dublin, Ireland, sent by Mrs. George Graham of Fort William (?) , Ontario, Canada, to Mrs. William A. Gaston of Boston, Mass. Mrs. Daly was a descendant of the Rev. Hugh Gaston. The children of Hugh Gaston are given in C. A. Hanna, Ohio Valley Genealogies (New York, 1900), 41. For notices of Hugh Gaston’s book see J. S. Reid and W. D. Killen, History of the

Presbyterian Church in Ireland (London, 1853), III, 355; and Allibone’s Dictionary of Authors (Philadelphia, 1888), I, 654.

- From a copy in the papers of Mrs. Irene McCreary Peden, preserved by Mrs. Jane Gaston Crawford, Chester, S.C. The spelling is therefore not the original.